Game Loop

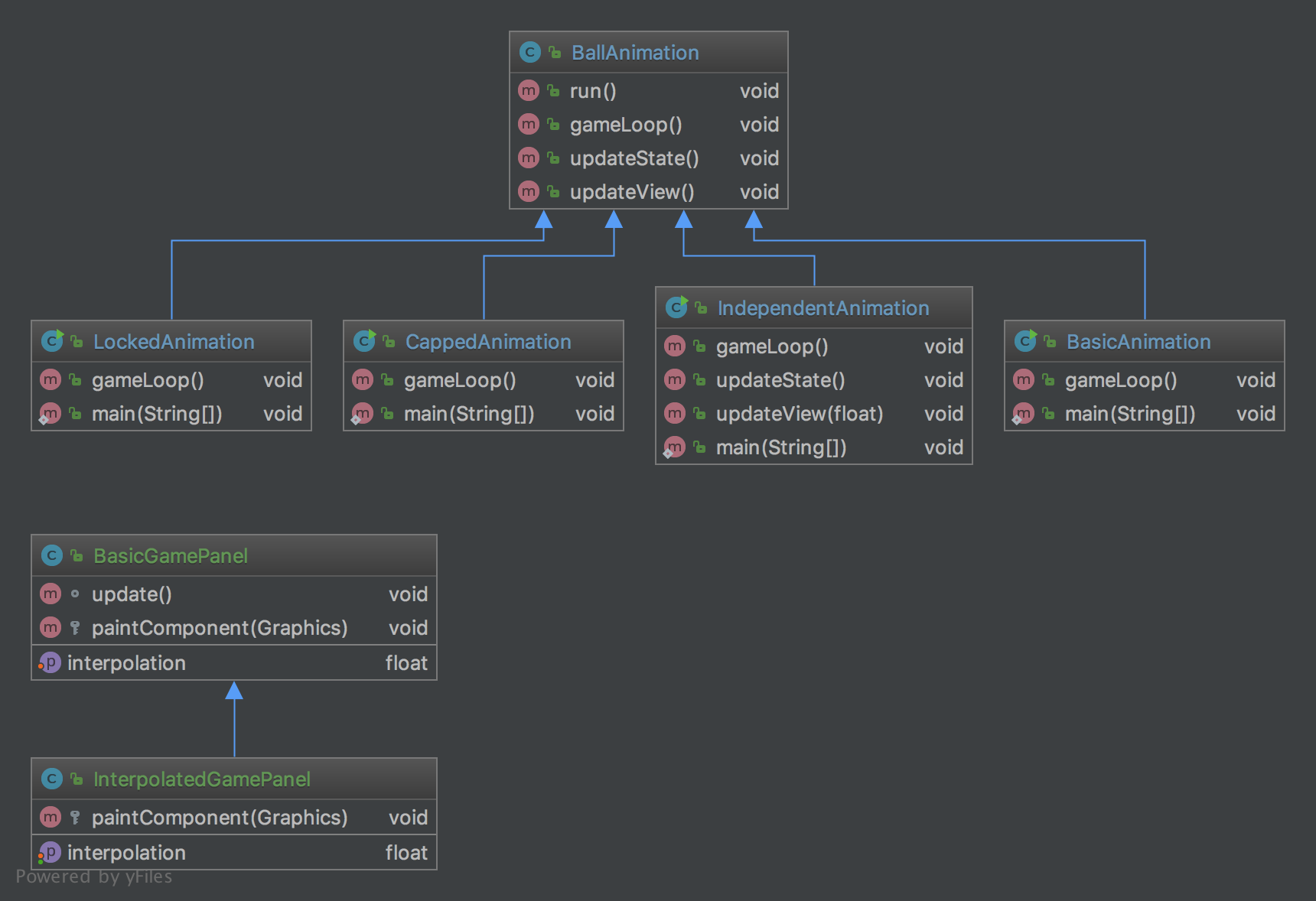

The Game Loop pattern is used when creating games, animations or UIs that need to update state irrespective of user input. This post will discuss the different implementations of game loops based on those found in my example project: Java Design Patterns / game-loop.

Implementations

Note: Game state is the real state of the game. Render state is the state of the display / render.

Basic

public void gameLoop() {

while (true) {

updateState();

updateView();

}

}

The basic loop updates the game state and render state at the same time. This means the game and render states are always the same. However, the basic loop is not limited and will simply run as fast as the hardware can handle. This is not useful as it means the game/animation will run at different speeds depending on the speed of the hardware.

Locked

public void gameLoop() {

final int framesPerSecond = 25;

final long skipTicks = 1000 / framesPerSecond;

long sleepPeriod;

long nextUpdateTick = System.currentTimeMillis();

while (true) {

updateState();

updateView();

nextUpdateTick += skipTicks;

sleepPeriod = nextUpdateTick - System.currentTimeMillis();

if (sleepPeriod >= 0) {

try {

sleep(sleepPeriod);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

}

The locked loop also updates game state and render state at the same time. To combat the issue of state updates being dependent on hardware speed, a frame-cap is set. This ensures that the loop will wait for a uniform interval between updates providing consistency across machines.

The issues with this implementation occur on slow hardware. If the hardware cannot keep up with the number of updates that need to occur per second to ensure a consistent experience, the loop will continue as soon as it can to try to meet the requirement. However, it will cause stutter in game and render states as updates slow down.

Another downside of the locked loop is that fast hardware will handle it well, but the hardware’s potential is being limited.

Capped

public void gameLoop() {

final long ticksPerSecond = 50;

final long skipTicks = 1000 / ticksPerSecond;

final int maxFrameSkip = 10;

long nextUpdateTick = System.currentTimeMillis();

int loops;

while (true) {

loops = 0;

while (System.currentTimeMillis() > nextUpdateTick && loops < maxFrameSkip) {

updateState();

nextUpdateTick += skipTicks;

loops++;

}

updateView();

}

}

The capped loop is the first of these example to allow separate updates of game state and frame state. In this case, a game state update-rate (ticksPerSecond) is set to ensure game state is updated consistently. In that sense, this implementation is similar to the locked loop.

In most cases, we can make the assumption that rendering a frame is more intensive than updating game state. Given this assumption, this loop ensures that if slow hardware is falling behind the update-rate, the loop will prioritise updating game state and stop rendering while it catches up. A ‘maxFrameSkip’ is often implemented to ensure that the game/animation does not just freeze on a single frame if the hardware is struggling to meet the update-rate demand.

This loop allows slower hardware to perform better than the locked loop. However, fast hardware is still bottle-necked by the update-rate – the frame-rate will never exceed the game state update-rate.

Independent

public void gameLoop() {

final long ticksPerSecond = 25;

final long skipTicks = 1000 / ticksPerSecond;

final int maxFrameSkip = 5;

long nextUpdateTick = System.currentTimeMillis();

int loops;

float interpolation;

while (true) {

loops = 0;

while (System.currentTimeMillis() > nextUpdateTick && loops < maxFrameSkip) {

updateState();

nextUpdateTick += skipTicks;

loops++;

}

interpolation =

(System.currentTimeMillis() + skipTicks - nextUpdateTick)

/ (float) skipTicks;

updateView(interpolation);

}

}

The most powerful loop in these examples is the independent loop. As the name states, this loop allows game state and render state to be updated independently of one another. Given the handicap of the previous loop, you may be wondering how it is possible to render more frames than there are game states. This loop achieves this via interpolation.

Interpolation produces a value used to understand what the game state would be equivalent to at an exact point between two real states. With the interpolation value, the render can make a prediction and produce a frame that would not actually exist given any real game state. As a side effect, the game state logic must be amended to take interpolation into consideration meaning this loop is not completely interchangeable.

To dive deeper into this concept, the source code and a working example of each loop can be found in the following Git Repository: Java Design Patterns / game-loop.